Biblical Existentialism and Marriage

An explanation and demonstration of Ratzinger's Method "C" Exegesis

I. On Scripture and the Catholic Faith

What is the place of Sacred Scripture in the Catholic Faith? How should Catholics engage with the bible and what presuppositions must they bring to such engagement? What, if any, value can they find in the work of modern historical-critical scholarship, which seeks to demystify the origins and cultural context in which particular texts of Scripture came to be written and received? How can we avoid a kind of magical thinking on the one hand, or a detached skepticism on the other, in order to make room for a living faith in a living God?

All these were questions of great urgency throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, as scholarly investigation into the origins of Scripture flourished outside of the Catholic Church, especially among German protestants, and as the Church became less and less of a temporal political authority in continental Europe and elsewhere, losing both the papal states and her privileges in various governments. Questions then, about the authority of Scripture in the life of the believer, dovetailed with a broader crisis of authority in the Western world and beyond.

Dei Verbum

The Church’s most definitive response to these developments came through the Second Vatican Council, in the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum, promulgated by Pope Paul VI. In it, the Church reaffirmed the doctrine that Scripture is divinely inspired, and that its primary author is the Holy Spirit, and so “must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation”1. At the same time, Dei Verbum added that since God speaks “through men in human fashion”, a faithful interpreter “should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words”2. With respect to the authority and place of Scripture in the Catholic faith, Dei Verbum gestures at an inseparable intimacy between “sacred tradition, Sacred Scripture and the teaching authority of the Church”, such that “one cannot stand without the others”3.

The Church here responds to the challenge of interpreting the mysteries and ambiguities of the bible with two salient principles. Firstly, that the Holy Spirit is both the primary author and interpreter of Sacred Scripture though He speaks in and through the words of men and likewise interprets in and through them. And secondly, that the Sacred Tradition as handed on through the ages, and the living magisterium of the Church, are both critical elements of its authoritative understanding. The first principle has an ancient pedigree; it is more or less an articulation of the “rule of faith”, appealed to throughout the controversies of the early Church and especially by St Irenaeus of Lyon in his polemic against heresies4. The second principle, though nascent among early Christians, presents a qualitatively different challenge to Christians in the 21st century where inherited tradition now spans two millennia and the living magisterium no longer share a singular hellenistic world but span global cultures and histories far more diffuse and varied. To the challenge of reconciling Scripture to itself as a cohesive whole, is now added the challenge of doing the same for centuries of magisterial teaching.

Further still, modern biblical scholarship raises even sharper challenges to the very possibility of reconciling these two principles. Modern Christians possess a much greater knowledge of the historical context and circumstances in which the books of the bible came to be written, and so what the sacred writers intended by means of their words, than did their forebears either patristic or medieval. Can such insights even be reconciled at all with interpretations of Scripture that have been handed on to us in the tradition?

Ratzinger, Erasmus Lecture and Method “C” exegesis

The late Pope Benedict XVI, himself a historical-critical scholar, was foremost among Church leaders to articulate and respond to these challenges. He had been present at the Second Vatican Council as a young theologian, and looked on as the crisis of exegesis grew more pronounced in the subsequent decades. His clarion call came in a famed Erasmus lecture, “Biblical Interpretation in Crisis”, delivered in 1988. In it, he described how the initial optimistic hope of historical-criticism, that “as the human element in sacred history became more and more visible, the hand of God, too, [would seem] larger and closer” gave way to discord and confusion5. Theologians, fearful to build their dogmatic systems on faulty interpretations of scripture, sought ever more to avoid contact with it altogether, preferring refuge in their systematic abstractions. Critics grew increasingly impatient with the hidden marks of limited humanity upon the text, seeking always to “remove all irrational residue and clarify everything”6. Scripture soon became a foil for Heideggerian existentialism, as in the case of Rudolph Bultmann, or for a Jungian psychodrama, as in the case of many contemporary biblical commentators like the atheist psychologist Jordan Peterson. Historians seeking the “historical Jesus” as someone other than or apart from the “Christ of faith” ever more erected fragile mosaics of their expectations out of the noise of archaeological evidence and ambiguous text. Amid this cacophony, a genuine encounter with Jesus Christ, the Living Word of God in the pages of Scripture seemed a growingly remote possibility, despite such an encounter remaining the explicit purpose of its composition. So says the evangelist in the Gospel of John: “these are written, that you might believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God; and that believing you might have life through his name” (Jn 20:31). The then-cardinal Ratzinger’s fundamental claim was that “the debate about modern exegesis is not a dispute among historians: it is rather a philosophical debate. Only in this way can it be carried on correctly. Otherwise it is like a battle in a mist.”7

Ratzinger concluded his speech with a set of hopeful guiding principles, a path out of the fog. He first exhorted scientific historiographers to retain a consciousness of the philosophical presuppositions they bring to bear on particular questions concerning the bible. One of these is to remain within a tradition that regards the bible, a collection of texts spanning more than a millennia in their composition by different authors in different cultures and written in different genres and languages, to be intelligible as a single book revealing a single man, the God-Man Jesus Christ who has entered history, died for the salvation of the world, and risen into glory that all may come to share in His life. He added that because Sacred Scripture is always received by and through the Church, it is necessary to retain the great bulk of patristic and medieval thought in contemporary discussions, rather than to attempt to circumvent them entirely with modern sources. He lastly emphasized the same principle that Dei Verbum had carried through from the early Church, that the hermeneutic of faith remains essential to encountering the Bible as a living Word. When he later became Pope Benedict XVI, he would return to all these themes addressing not only biblical scholars but the whole body of believers in his apostolic exhortation Verbum Domini, on the place of the Word of God in the life and mission of the Church.

Ratzinger eventually compressed these guiding principles into what he termed a “Method C” exegesis, describing a synthesis of the patristic and medieval “Method A”, which prioritized the spiritual revelation of a passage of Scripture in the light of Christ, with the contributions of a “Method B” that pursued a richer understanding of the original intent and context of a particular text and the audience that would have initially received it.

There is a sense in which many of the controversies surrounding “Method A” in the history of the Church all revolve around the mystery of biblical inspiration. What does it mean for a text to be inspired? To teach without error? How do we understand which interpretation is the “inspired” one, especially if two potential readings contradict? What are the relevant senses of scripture? How do words work as signs? What are signs?

Perhaps analogously, the many controversies that have surrounded “Method B” exegesis seem to revolve around the mystery of biblical providence. How can we trust God willed to give us the Bible as we’ve come to receive it? Which translations and redactions reliably retain and transmit what God has given the Church through history? How and when can we view books of Scripture as works of history when their methods of composition are so alien to the modern discipline of history? Ratzinger in a later work, Principles of Catholic Theology, called this grappling with the “mediation of history in the realm of ontology” the “fundamental crisis of our age”8.

Framed this way, Ratzinger’s synthesis of the two methods is then haunted by the relationship between these two, that is, between inspiration and providence. But what might it look like? What light might this two-pronged approach to scripture uniquely shed on the mysteries of human life? Let us here below attempt to demonstrate this approach in considering one such question: “Which is existentially prior, marriage or political community?”

II: On Marriage and Political Community

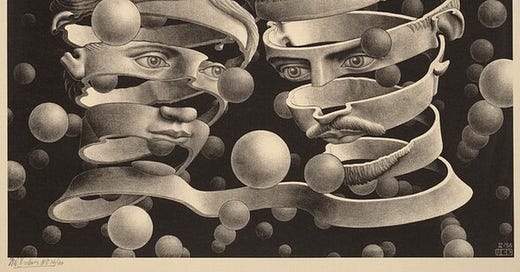

In our considered experience, these relationships confront us almost in the manner of an Escher drawing, with each preceding the other. On the one hand, the philosopher Aristotle recognizes man as a political animal, that it is natural and inherent for man to exist in a political community, and a person truly set apart from any such community is something other than a man9. On the other, it is through the particular relationship of man and woman that any of us come to be, and so that relationship is in some important sense our immanent existential origin. We enter the world not firstly as citizens of a polity but as dependent children of a mother. Though marriage in some form is ubiquitous, cultures and particular communities govern the rites and obligations which make marriage legible, and in this they differ enormously. At the same time, marriage and its offspring are the means by which those cultures and communities come to be and to continue themselves. There are stakes to this priority, since intuitive disagreements about it inform opposing views about the limits and responsibilities of political authority and the primary responsibility for educating children. What might Scripture illuminate?

Creation Accounts and the Decalogue

We can begin with the two creation accounts in Genesis 1 and 2. In the first, God creates man at once male and female in His image and likeness, and gives them a mandate to “be fruitful and multiply” and to replenish and subdue the land (cf. Gn 1:27-28). Here man’s primordial relationship is that of male and female, and it’s paired with a priestly mandate to reproduce and to renew the earth.

In Genesis 2, the first man is made from the dust of the earth, in a condition that the late Pope St. John Paul II called his “original solitude”10 (cf. Gn 2:7). All throughout creation, God has until this point looked upon what he had made and deemed it “good”, but when He gazes upon man’s solitude, He says it is “not good for man to be alone” (Gn 2:18). After having the man name all the animals, and finding them each ill-fit companions, God draws woman from the man’s side and when he sees her he declares her “at last, bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” and the inspired author proceeds to tell us that “therefore a man shall leave his mother and father, and cleave to his wife, and the two shall be one flesh” (Gn 2:23-24).

In these two short accounts, we are given a terse encounter with what the Catholic Church teaches are the two inseparable ends of marriage. The first, though not explicitly invoking marriage, pairs the creation of man and woman with their procreative end in the mandate to be fruitful and multiply. The second, in describing the relationship of spouses as becoming “one flesh”, makes clear its unitive end. While the first narrative omits a direct mention of marriage, the second omits any reference to the begetting of children.

By contrast, it is not until later in Genesis 4, after Cain’s killing of Abel, that we get mention of his founding of the first city, named after his son Enoch (cf. Gn 4:17). In the Genesis narrative, Aristotle’s primal template for the political community has already been preceded by two weddings and a funeral. Cities in Genesis go on to be models of man’s pride, such as Babel in Genesis 11, or man’s depravity, such as Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19. At first glance it seems that Scripture affirms a priority of marriage over the wider political community, both with respect to man’s origins and with a more unambiguous affirmation.

We may add to this perception in considering Exodus 20 and the giving of the law. The children of Israel, after being liberated from Egyptian captivity and brought into the wilderness of Sinai, receive God’s law from Moses. Jewish and Christian tradition alike ascribe a pride of place to the first ten commandments, termed the decalogue, as an expression of enduring and universal moral law, in contrast to the more contextual and particular injunctions that follow them. The Catechism of the Catholic Church says they contain the “principal precepts” of the natural law, written on the heart of every man (cf. CCC 1955-1956).

The decalogue includes three injunctions concerning man’s relationship to God: to have no other gods, not to take His name in vain, and to keep the sabbath holy (cf Ex 20:2-10). The remaining seven concern man’s relationship to other men. Most of these are universal in that they do not concern how one ought to treat persons on account of a particular relationship (such as fellow citizens, countrymen, etc..) but how to treat any other persons in an undifferentiated way: we are not to kill, to steal, to lie, or to covet the goods of others (cf. Ex 20:12-13). However, the 4th commandment to “Honor thy mother and father” and the 6th proscribing adultery do implicate particular relationships, that of a child to their parents and that of a spouse. Here the most universal moral precepts intrinsically entail particular familial relationships and marriage, but not those which otherwise constitute political community, perhaps again implying that there is something more fundamental and less contingent about the former.

Babylonian Exile

But can the historical context of these texts and the community of their initial reception shed further light on what they have to say to us? Though most early tradition implicitly attributes authorship of both Genesis and Exodus to Moses, the modern consensus of scholars and historians is that they were finally redacted into the form that we receive them in following the Babylonian exile of 586-539 BC11. This was the time from when king Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon had ransacked Jerusalem, destroyed the temple, and dispersed much of the kingdom of Judah from their land. They remained in exile until king Cyrus of Persia defeated Babylon and allowed the Jews to return and rebuild their temple. Though assuredly drawing on older tradition both oral and written, it is here at Israel’s lowest point, lamenting the loss of their land and temple, that they come to finally assemble the sacred texts that reveal their God to them.

This is a notable oddity in the ancient world. Generally various peoples are fair-weather friends of their gods, devoted insofar as they are rewarded and the gods that fail to reward them are just as soon abandoned. Israel instead discovers and renews her devotion to her God in the wake of disaster, finding fault instead in her own infidelity. It is important to note that the prophet Ezekiel, a contemporary of the events precipitating the exile, depicts this relationship between God and His people in explicitly nuptial terms (cf. Ez 16). It’s just as they’ve lost everything that Israel comes to understand that the God who had chosen her is not just one god among many but is instead the creator of all heaven and earth. Much of the creation narrative in Genesis is informed by, and seemingly polemically responsive to, a similar Babylonian creation myth in the Enuma Elish, in which the god Marduk makes the world in an act of primordial violence by slaying the goddess Tiamat12.

But it’s also during the Babylonian captivity that a different city, Jerusalem, becomes a great object of Israel’s longing, especially as expressed in the psalms. The psalmist laments weeping over Zion, declaring that if he were to forget Jerusalem that his right hand should wither and his tongue cling to his mouth (cf. Ps 137:5-6). He yearns for the temple, singing “As the sparrow finds a home, and the swallow a nest to settle her young, my home is by your altars” (Ps 84:4). Many of the psalms, like the creation account in Genesis, were composed during and with explicit reference to the Babylonian captivity. Israel has a destination and a home, not just in a garden past, but in a city of God. While she is dispersed and in exile, her prayers come to center on the hope that her God will deliver her from her captors and return her there, and it’s in the context of that hope that she comes to recognize Him as the creator of all.

What can this history help us to understand? For one, while we read sacred history naturally as a story of creation, fall, and redemption, Israel’s self-understanding begins in media res, working back from faith in a savior God to a recognition that He is the Creator. In a salient experiential sense, salvation is prior to creation. Nuptial imagery in the prophets also gives marriage an anagogical significance, it expresses something about God’s fidelity and likewise about man’s infidelity. It’s through contrition over their sin that Israel comes to trust again in God’s faithfulness.

But at the same time, the locus of salvation and the shared end at which Israel aims and hopes, is not a marriage but a renewed city, Jerusalem. What begins in marriage has its end in the city and the temple, in worship and praise of God. Perhaps in a teleological sense then, the city and the worship that draws it together and centers it, are prior to marriage in the manner that an end is prior to an act. In and through His covenant, God draws His people together in community to worship Him.

Lastly, to almost state the obvious, it reminds us that God’s revelation is received by an already extant political community, with a language and some prior sense of their collective identity. Even if familial relationships are prior or more fundamental than particular political arrangements, it takes an existing political community to receive and transmit that understanding, and so to foster and govern those relationships and to make them visible and intelligible. In attending to both Scripture’s spiritual significance and its historical context, it seems we may have returned to our Escher drawing after all.

The New Covenant

But perhaps not. Lastly, it would be irresponsible to attend to any question about the teaching and meaning of Scripture without attention to Jesus Christ, at whom all revelation ought to direct us and through whom the fullness of the truth is made known to us (cf. Jn 14:6). This is necessary if we are to apply Ratzinger’s principle which treats the whole of Scripture as a singular testimony and “accepts the Bible as a book”. What then does Jesus have to teach us?

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus has two notable discourses on the subject of marriage. The first is with the Pharisees, who interrogate Him concerning the lawfulness of divorce. He cites Genesis 2, that the two have been made one flesh, and adds “therefore what God has joined together, let man not separate” (Mt 19:6). When they respond asking Him why Moses permitted divorce when He gave the law, our Lord demonstrates an example of a principle faithful historical-critics make frequent use of, that of divine pedagogy. He tells them, “Moses, because of the hardness of your hearts, permitted you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so” (Mt 19:8). Salvation history involves a growing spiritual maturity among God’s people, and evils He may concede to permit them at one time, such as divorce or slavery, He will ultimately lead them to reject. In this process, it is never God who changes but man. The prelapsarian will of God revealed in the Creation narrative of Genesis 1 and 2, and the earthly life of His perfect Divine Son testified to in the Gospels, both remain reliable witness to eternal and unchanging moral truths about reality, even if some of the laws and commands by which God governed the Israelites in salvation history do not.

After this exchange, His disciples say to Him that if marriage is so severe, it seems better not to marry. He replies that all cannot accept this teaching, and exalts celibacy saying that while some have been born eunuchs, or made eunuchs by men, others “have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of God” and that “He who is able to accept it, let him accept it” (cf Mt 19:11-12). It’s notable also that this whole episode is immediately followed by His injunction that His disciples “let the little children come to [Him]” (Mt 19:14). Perhaps again we have the evangelist linking discussion of marriage with a reminder of its procreative end, while at the same time seeming to diminish its place in the order of things.

The second marriage discourse is with the sadducees, who doubt that there will be a resurrection of the body, and use a story of a woman with several consecutive husbands as their foil. Who, they ask, will be her husband in the life to come? Jesus answers that they do not know “the Scriptures nor the power of God. For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like the angels of God in heaven” (cf. Mt 22:23-29). Though marriage was with us since the beginning, it will not be with us in the end. What about political community?

Near the end of John’s Revelation, the final book of the New Testament, the author describes a vision of the end of the world in this way:

“Now I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away. Also there was no more sea. Then I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a Bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice of heaven saying “Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men, and He will dwell them, and they shall be His people. God Himself will be with them and be their God. And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there shall be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more pain, for the former things have passed away.” Then He who sat on the throne said “Behold, I make all things new” (Rv 21:1-5)

Giving and taking in marriage belongs to the world that is passing away, but the world to come will be in a city, and a city that comes “as a Bride adorned for her Husband”. The coming of the New Jerusalem is like the consummation of a marriage, that of God and His people forever. The story which began with a marriage in a garden ends in a city, wherein we are not spouses but friends and children of God. In the light of Christ, though both marriage and polis are bound up together, we are no longer caught in an Escher-like loop.

Concluding Remarks

Much more could be said. But these initial gestures serve to demonstrate one possible way that attention to its history and original intent could be a complement to serious spiritual reflection about Scripture. It’s worth noting too that this notion is not entirely modern or novel. The medieval scholastic Hugh of St Victor, for instance, was keenly concerned in his commentaries with the historical context and culture of the ancient Hebrews, expecting that such knowledge would help him to better penetrate the text.

Scholarly consensus, especially concerning ancient history, is ephemeral. In taking contemporary scholarship seriously, theologians should not thereby make particular notions in the field too load-bearing, lest they import the epistemic crisis of the natural sciences even more thoroughly into theology. But if Scripture points us to anything about reality, it’s to God’s special action in time, most particularly in the Paschal mystery. If we are able to bring a hermeneutic of faith to the mysteries of Scripture, we may tentatively do the same to the providential context in which it came to be written and compiled. And what draws these perspectives together, what makes them one cohesive whole instead of a cacophony of unmeetable ends, is the light of Christ, who we seek to encounter both through God’s word and today in our present condition.

One last thought about the particular topic of our inquiry. Though we turn to Scripture to nourish our own spiritual lives, we also do so to inform and renew the life of the Church, and we should expect the insights we draw to have some relationship to the way the Church is constituted here and now. As noted at the outset, the authority of Scripture and that of the Church are intimately bound up together. It can be further said that the Church regards both marriage and holy orders as sacraments, mysteries that signify and make present the efficacious grace of the living God. These two sacraments in particular constitute how the Church exists as a body in and through particular relationships, in a way that mirrors the tension we’ve considered here. For while the Church sanctifies marriage as Christ did, she also continues herself through a hierarchy of men who almost all remain unmarried and father no children of their own. Just as we may contemplate the creation story and teachings of Christ in considering an existential mystery, we can likewise contemplate the mystery of the Church in her sacramental economy, here and now present to us. God willing, each may deepen our appreciation and understanding of the other.

Header image is “Bond of Union” by M.C. Escher

Dei Verbum: "De Divina Revelatione: the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation of Vatican Council, Promulgated by Pope Paul VI, November 18, 1965.” 11

Ibid. 12

Ibid. 10 (Notably, while the English translation leaves “sacred tradition” and “teaching authority” uncapitalized, the original Latin capitalizes “Sacram Traditionem” and “Ecclesiae Magisterium”, perhaps suggesting a higher view of their parity with Scripture than the English translation conveys)

Irenaeus of Lyon speaks of a “Rule of the truth…received by means of baptism” for interpreting scripture (Against Heresies, 1.9.4)

Biblical interpretation in crisis. First Things. https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2008/04/biblical-interpretation-in-crisis

Ibid.

Ibid.

Pope Benedict’s theological legacy: An Augustinian at heart who influenced the course of Vatican II and beyond. (2023, January 19). America Magazine. https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2022/12/31/pope-benedict-theology-obituary-225604

Cf. Aristotle’s Politics Book I Part 2

General Audience, 10 October 1979 - The Meaning of Man’s Original Solitude | John Paul II. (1979, October 9). https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/audiences/1979/documents/hf_jp-ii_aud_19791010.html

Ramage, Matthew J. From the dust of the Earth: Benedict XVI, the Bible, and the theory of evolution. Washington, D.C: The Catholic University of America Press, 2022. pg. 131-132

Ibid.